The Substance: Don't beat yourself up!

An essay on dualism, symbolism, and culture myth in The Substance (2024).

The Spoiler Plate

If you intend to, please watch the movie before you read this, as it contains LOTS of spoilers and really is meant for people who have seen it (rather than a review to influence whether you’ll watch it or not). I examine themes built from moments at different parts of the film, so prepare for a non-linear recount of the plot.

Disclaimer: I wanted to write my thoughts more than edit them, so I’m sorry if it’s a little clunky…

Also, I’m no expert. Nor a doctor. At the most I’m pretending to be a Robert Langdon-type, but for movies. At the least, I’m a guy who likes to watch things and Google stuff.

Okayyyletsgoh

There’s always cautious excitement when a satire with an ultra-modern premise drops; a beach that makes you old, an AI doll that takes friendship too far, a haunted Zoom call, or a video game where you play a streamer terrorised by a parasocial stalker. In this case, Coralie Fargeat’s body-horror The Substance evokes the ageist treatment of women in showbiz, self-image, and society’s obsession with youth. The setting? Ground zero: Hollywood.

The Substance is both intricate and crude in its portrayal of Elisabeth Sparkle, an actress-turned-aerobics instructor clinging to the twilight of her career, which a producer snuffs-out as she turns 50. As the saying goes: “This business, this town, it chews you up, then spits you out.”

Thereafter, it’s desperate times. And we all know what those things call for.

Final warning: spoilers

Final warning: spoilers

Final warning: spoilers

Final warning: spoilers

Final warning: spoilers

Final warning: spoilers

Final warning: spoilers

Final warning: spoilers

Final warning: spoilers

Final warning: spoilers

You’ve been warned.

The Personality Splits: Dualism

Dualism most commonly refers to:

Cosmological dualism: the belief in only two fundamental, opposed concepts, like "good" and "evil."

Property dualism: the idea that, though the world is composed of one kind of substance (the physical kind), there are two distinct kinds of properties: physical and mental.

Mind–body dualism: the view that mental phenomena aren’t entirely physical or that the mind and body are distinct and separable.

These concepts introduce a complexity beyond “young and old“ or “living a double life“. French director Coralie Fargeat materialises, not just two characters, but two worlds at odds. She constructs a volatile atmosphere that shifts between division and unity, balance and imbalance, to mirror her characters’ struggles.

Fargeat builds tension by referencing ideas that coexist, oppose, and sometimes align: Jungian vs. Freudian theory, religion vs. science, Christianity vs. Judaism, ancient vs. modern, preservation vs. transformation, inside vs. outside, nature vs. nurture, and Eastern vs. Western.

Nomenclature

Elisabeth Sparkle: A first and second name, probably a stage name, anchors Elisabeth to social norms, tags her as the protagonist, but suggests that her identity is a facade. The spelling “Elisabeth,” which is most commonly spelled ‘Elizabeth’ in English-speaking countries, hints at the dual nature of her identity and positions her as a fish out of water, and perhaps, an ugly duckling.

The name traces its origins back to Hebrew, where it stems from the name Elisheva. In Hebrew, Elisheva is composed of two elements: el, meaning God, and shava, meaning to swear or oath—”Oath to God”. In the Bible, Elizabeth is the mother of John the Baptist—a prophet, destined for significance—she’s a vessel in service to a higher power, just as Elisabeth is a vessel, bound to Sue, her career, Hollywood, and The Substance. It signals a lack of agency; her fate is sealed. She’s a victim of circumstance.

As far as the name “Sparkle” goes, she’s a star, and stars die by imploding.

Sue: A mononym suggests singularity, otherness and a way to detach her from conventions; the name Sue is ordinary, but as a mononym, she’s extraordinary. The name’s Hebrew origin is derived from “Shoshana” (Susanna), which means “Lily”—symbolising purity, beauty, and fertility. It can also mean “Lotus Flower,” holding similar connotations, as well as “rising from the mud without stains.” It would seem that Elisabeth is the mud.

Sue is immaculate and hyper-sexualised through the male gaze, with a hint of superhero energy. A divine energy.

In the Book of Daniel, Susanna is a virtuous woman who is victimised by two lustful elders who spy on her while she bathes—a metaphor for the male gaze, and for age as her antagonist. Sue is a product of male ideals and operates in a patriarchal environment where they too can abuse their power.

It’s documented that the name Neo in The Matrix is an anagram for “One,” foreshadowing his destiny as The One. “Sue,” an anagram of “use,” suggests her role in the story and society—as a noun, she’s of use to Elisabeth and Hollywood. As a verb, she’s an instruction—use her. Exploit. Consume.

Matrix: “You are the matrix. The matrix is you.” A matrix is “something within or from which something else originates, develops, or takes form”; Elisabeth is the biological matrix for Sue.

This shot frames Sue’s lips as a mathematical matrix made of screens, emphasising her unnatural, commodified qualities.

Substance: Definitions of “substance” frame things pretty neatly.

Real, tangible matter; Elisabeth

The essential part or meaning; “Have you ever dreamt of a better version of yourself? Younger, more beautiful, more perfect.”

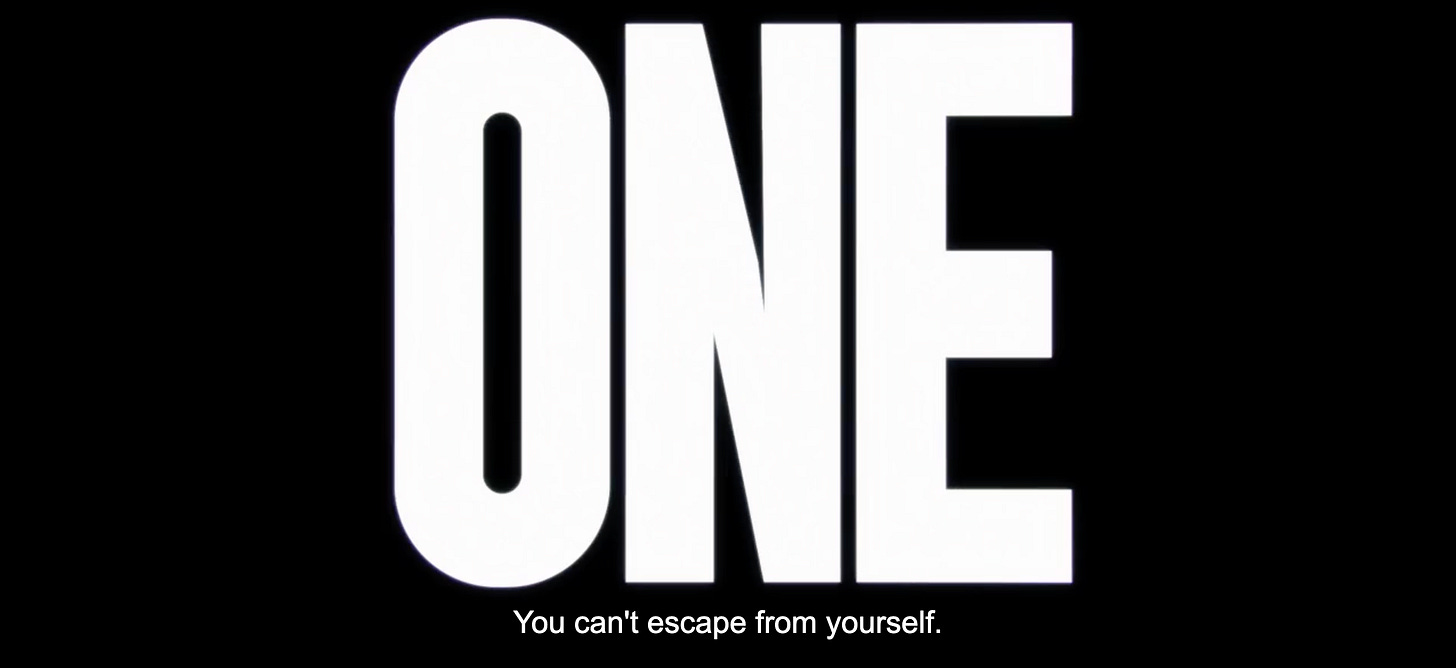

The quality of importance, validity, or significance; “You cannot run from yourself.”

The quality of having a factual basis; “You are the matrix. The matrix is you.”

Playing God: Science vs religion

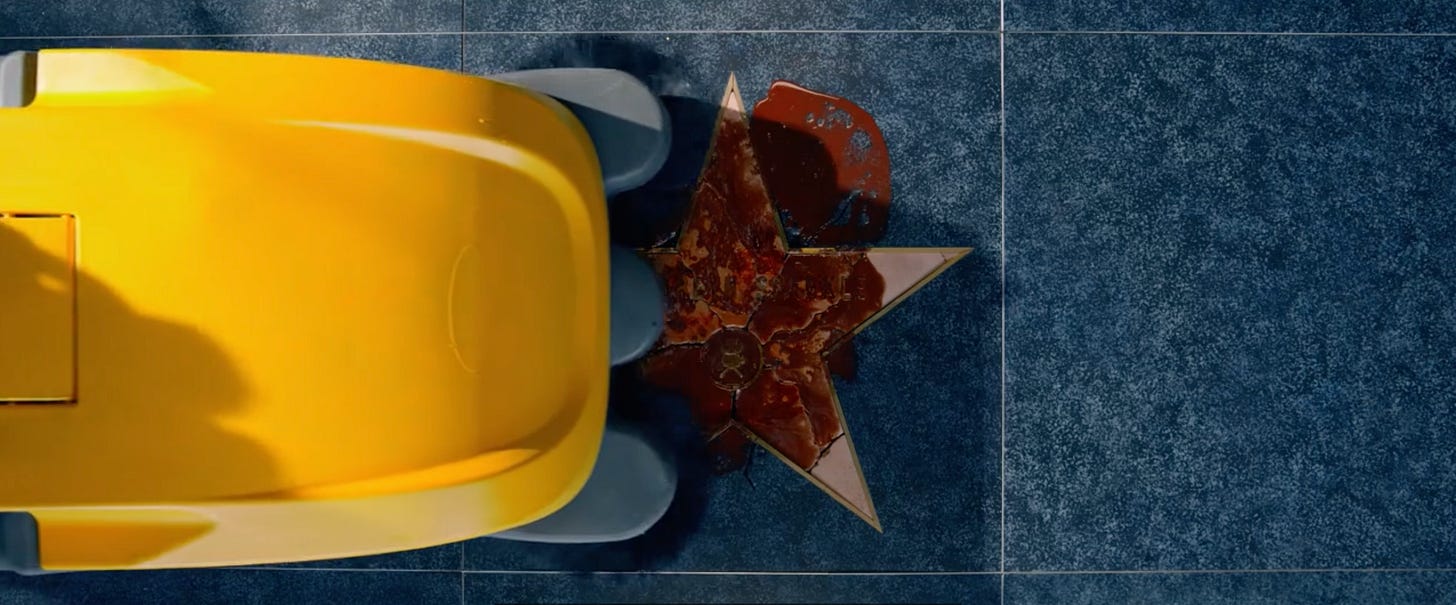

The movie’s opening introduces dual metaphors for genesis and transformation: First, a perfect egg is injected, duplicating the yolk. Followed by a somewhat ‘primordial soup’ evolution of Elisabeth’s star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. It can be interpreted as the creation of the universe; from a scientific perspective—The Big Bang—as well as the biblical perspective; Genesis.

The sequence breaks the fifth wall with a ‘God’s eye’ shot, casting the audience as a divine creator and witness, hinting that we play a role in what the story is about.

The shot is also known as “Bird’s eye,” perhaps a nod to the Greek myth of Icarus, hinting at the perilous ambition of both characters.

Beginning as a literal clean slate, Elisabeth’s star evolves and transforms, signposting different stages of Sparkle’s career; a literal stage where she poses for cameras…

a shrine, worshiped by fans…

and finally, a weathered plaque, cracked and bloodied with waste.

This is terrific exposition that involves almost no dialogue. The star enshrines the peak of Elisabeth’s career and reveals its vulnerability to the harshness of time. It sets up the idea of dual worlds, tells us everything we need to know about the protagonist, her arc, and establishes the cultural context of the plot.

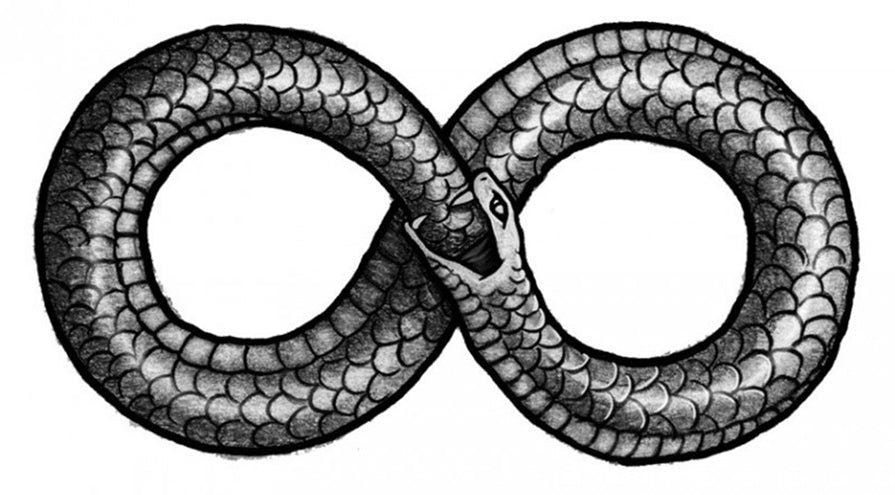

The Self-Eating Snake: Eggs, Chicken, Eyes & Ego

Eggs, chickens, and yolks symbolise creation, new life, and fragility. The colour yellow and the chicken also reflect cowardice; Elisabeth’s fear of judgment.

In Christianity, eggs mean ‘God’s blessing,’ closing the loop between the meaning of Elisabeth’s name—pledge to God. Some view eggs as a metaphor for the Holy Trinity: the shell, the white and the yolk.

God is the shell, the yolk is Jesus and the Holy Spirit is the white. Each is essential to the other and together, they make up an egg – a symbol of birth.

Elisabeth is framed here as a yolk at the centre of the pure white shell of The Substance pickup location.

Sue is framed here like a baby chicken, pecking her way through its shell.

The chicken is also a flightless bird, perhaps an extension to the Icarus theory, stretching to the idea of ignorance, defying limits, and greed. Elisabeth continues to transform as Sue breaks the rules of the The Substance—her penultimate form is somewhat troll-esque, but also not unlike that of a plucked chicken.

After the first seven day cycle of using The Substance, we see Elisabeth return to consciousness, followed shortly by her frying and consuming a couple of eggs. There is a myth that you should never feed eggs or egg shells to chickens, as it causes them to develop a taste for their own eggs. With this, Fargeat sparks the notion of The Substance as an unsustainable, self-destructive routine; Elisabeth is eating away at herself, a la the “self-eating snake,” a metaphor for infinity, cyclicality and other loop phenomena that are often self-destructive in nature.

Of course, chicken is also meat—white meat—the meat most consumed by the western world. Now we’re thinking about capitalism and western ideals for beauty. There’s plenty of edits that cast the characters as both the meat and the consumer.

While piggishly eating shrimp, Harvey seems to refer to menopause—”it… stops…” Considering the egg and chicken motifs, this would liken Elisabeth to a retired battery hen, heading for the chop. Pretty grim.

Then there’s the age-old conundrum about evolution: “Which came first, the chicken or the egg?” A provocation that serves as a blueprint for Elisabeth’s descent into madness as she becomes more and more dissociated from Sue (herself).

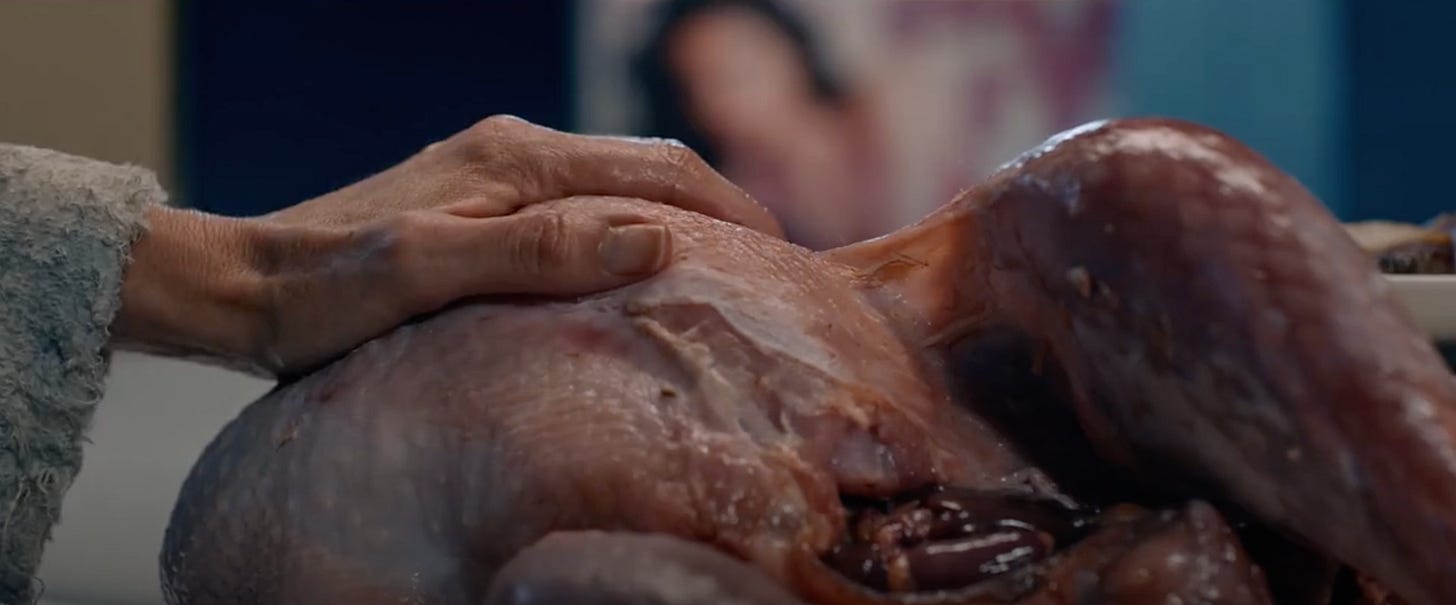

Sue also embodies the chicken—a fertilised egg’s final form—fully realised, conscious, liberated, but vulnerable. She is more often than not associated with chicken as a meat product; fresh meat for the grinder of Hollywood (and, humorously, her youth would also make her a ‘spring chicken’). It’s driven home when she appears to pull a cooked chicken drumstick from her navel, which we also know to be a baby’s first ‘mouth’. It reminds us that she’s tethered to Elisabeth by this destructive cycle of consumption; what is consumed by one has consequences for the other. The Switch is even like an umbilical cord. A lifeline that facilitates a tug-of-war, as Sue steals more time from Elisabeth, upsetting the balance.

In a very witchy state, Elisabeth obsessively cooks up a feast, including “boudin aux pommes” (blood sausage with apples). “Boudin” is French slang for "ugly girl,” reflecting her self-loathing. Leaning into a Snow White / evil hag vibe, the apples would represent her intent to sabotage Sue (Snow White), and eventually terminate her. Apples also hark back to the old testament as a symbol of Eve’s temptation and original sin, worthy of punishment.

The Christmas turkey recipe has dual symbols for Sue; it signals birth and sacrifice; the birth of Christ and the sacrificial bird at Thanksgiving. It’s also reminiscent of the betrayal and displacement of a nation’s indigenous people—America’s true self. Sue acts as a sort of coloniser of Elisabeth’s apartment, occupying and transforming the landscape to suit her needs, and hiding Elisabeth from sight.

Out of sight, out of mind, out of her mind.

An egg is also a Freudian metaphor for human consciousness, consisting of three parts, the Id, the Ego and the Super Ego. Freud believed that the self was a by-product of ego development. By contrast, Jungians believe the self is present before the ego; it is primary and it is the ego that develops from it.

In Jungian psychology, the "Two-Centred Hypothesis" suggests that personality has two main centres: the ego and the Self. The ego is the centre of our conscious mind, while the Self represents our entire personality, including both conscious and unconscious parts. Imagine the ego as a small circle within a larger circle, where the larger circle—the Self—represents the whole personality. Both share the same central point, but they can be seen as different points. Sounds like an egg, right? Perhaps also an eye which is responsible for the literal self-image and known as the window to the soul.

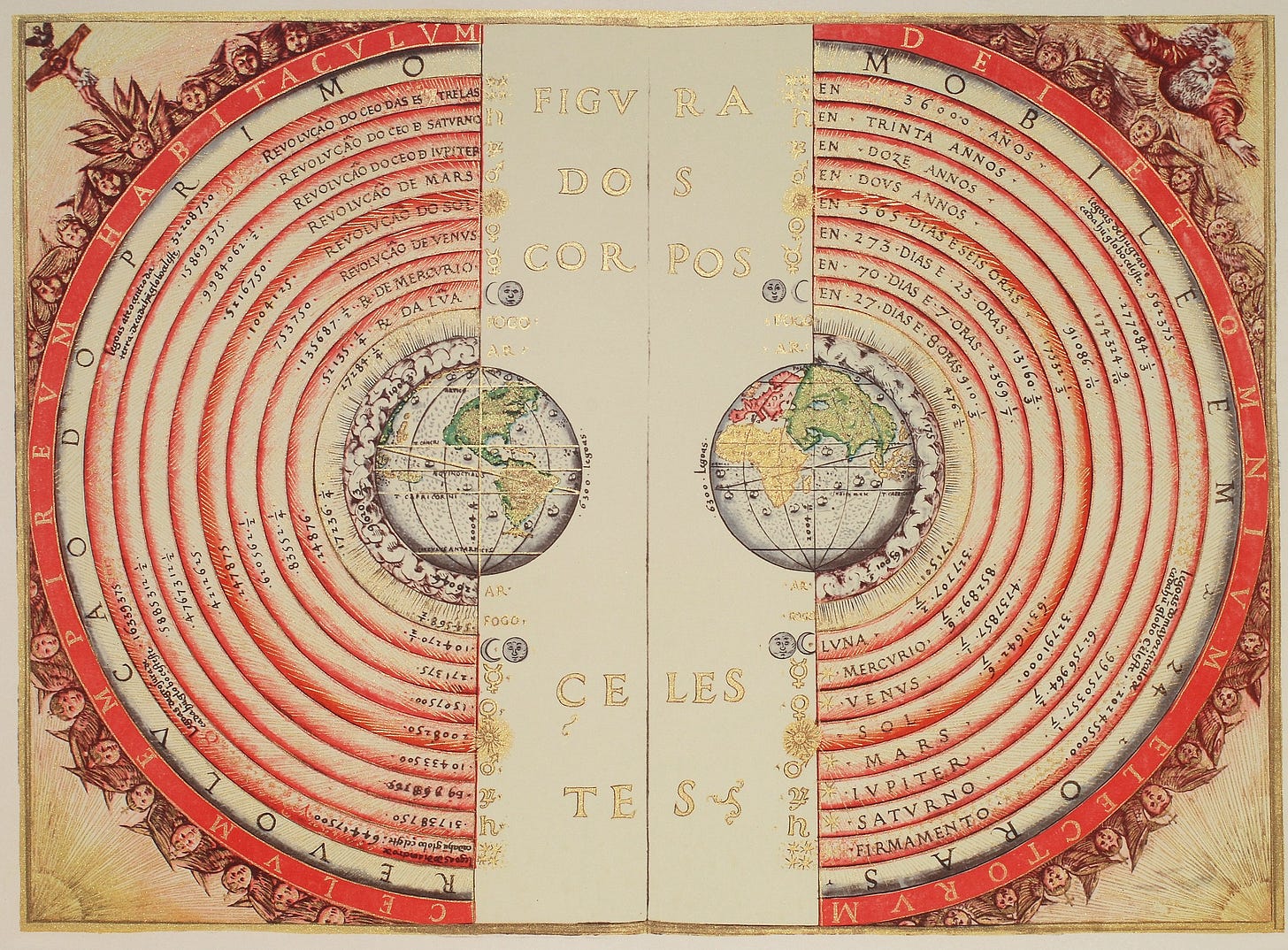

There are similarities to the Geocentric model, which illustrated the belief that the earth was the centre of the universe. Once again, we see dualism in knowledge vs ignorance, introspection vs existentialism, and the idea of inner and outer worlds.

Fargeat plays with the nuances of consciousness. When Elisabeth is unconscious, she seems to appear as though she is dead; contorted, uncomfortable, and undignified. Often with her eyes still open…

Whereas Sue’s unconscious self seems more like she’s sleeping; poised, peaceful and angelic—even after she’s been dragged around the house…

Jung's concept of the “Emergence of the Self“ suggests that everyone is born with a natural sense of wholeness. As we grow, a separate sense of ego develops, marking the main task of the first part of life. However, Jungians believe that mental well-being also requires reconnecting with this original sense of Self, often through myths, initiation ceremonies, and rites of passage. This can be interpreted as The Stabilizer and The Switch.

In JMW Slack’s Egg & Ego, the "Egg" in the title refers to developmental biology, the author’s field and source of anecdotes. "Ego" speaks to scientists' vanity, as they must secure funding by convincing peers of their excellence. Slack says that success often favours those with the largest egos, whose methods are described in this book. This reinforces the idea of a system that sustains itself through image rather than substance.

Japanese Author Haruki Murakami compared humans to eggs in his acceptance speech for the Jerusalem prize.

"If there is a hard, high wall and an egg that breaks against it, no matter how right the wall or how wrong the egg, I will stand on the side of the egg. Why? Because each of us is an egg, a unique soul enclosed in a fragile egg. Each of us is confronting a high wall. The high wall is the system which forces us to do the things we would not ordinarily see fit to do as individuals."

Sue’s main motive is hosting the New Years Eve Show. NYE evokes the idea of time and inevitability, which both characters are victims of. It becomes Sue’s final, futile attempt at rejecting and escaping Elisabeth—her true self—but as The Substance warns: You can’t escape from yourself.

Biblical Proportions: Good vs Evil

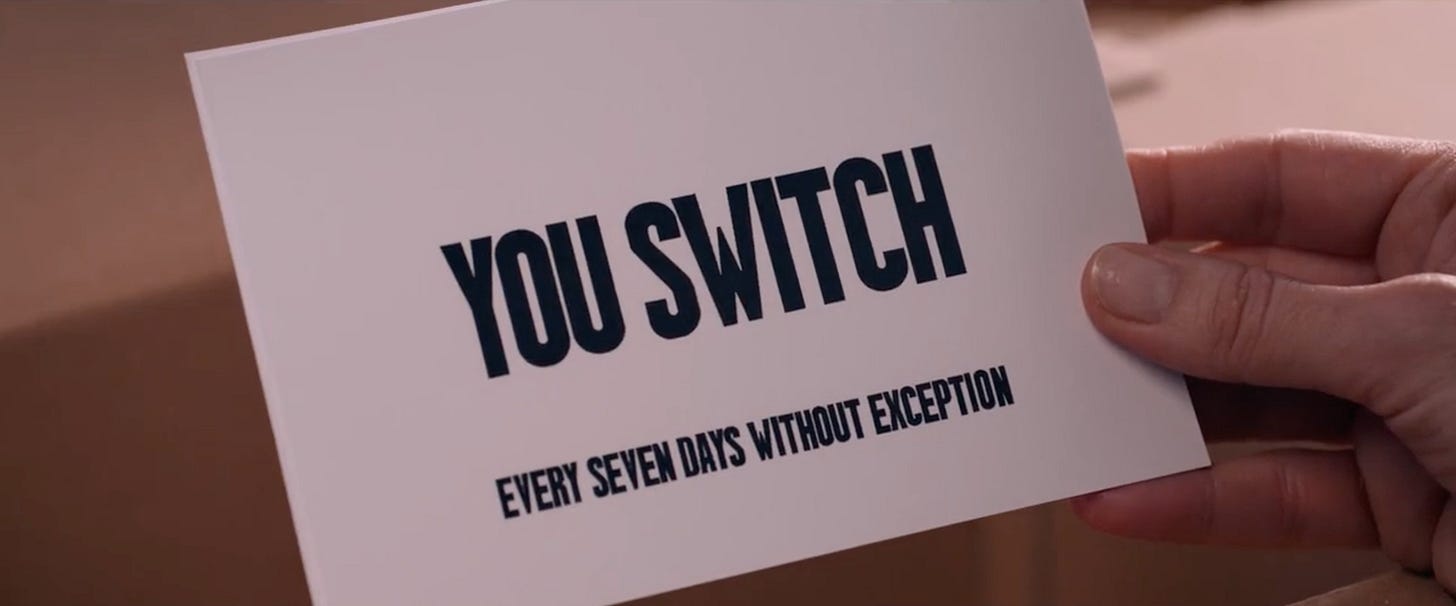

There are many references to the old and new testaments, again reinforcing this tension and balance between ancient/origins, modernity/newness, good/evil, rules/deeds. The weekly routine for The Substance nods to the biblical creation of the world in seven days. Each day is punctuated with Sue’s reliance on The Stabiliser—a daily prayer—and once a week, The Switch—a visit to church to be closer to God.

Elisabeth can be seen as an Adam-like figure, with Sue (Eve) being created from Elisabeth’s body/matter. And like Eve, Sue gives into temptation and strays from the rules. Perhaps The Substance paraphernalia and the strict rules act as a sort of Ten Commandments.

We see the seven deadly sins portrayed in various forms:

Covetous

Vanity/Pride

Lust

Envy

Sloth

Gluttony

Wrath

And then there’s this little nugget that flashes before Sue becomes conscious - a seal that forms a partition between Elisabeth and Sue’s consciousness. What does a flaming heart symbolise?

Devotion and Sacrifice: In religious contexts, especially in Christianity, the burning heart (often depicted as the "Sacred Heart" of Jesus) symbolise profound spiritual love, devotion, and sacrifice. The flames represent unwavering dedication to humanity and the willingness to endure suffering for others' sake.

Spiritual Awakening or Transformation: A burning heart can symbolise inner transformation, spiritual enlightenment, or awakening. The fire represents purification and a deepening of one’s connection to spirituality or personal purpose.

After Sue’s first seven day cycle, the montage ends with a shot of her looking out the apartment window. She’s wearing a kimono emblazoned with a dragon, a symbol of supernatural power, transformation, chaos, untamed nature and evil; foreshadowing Sue’s arc. It’s also emblematic of cultural appropriation, reminding us of ignorance and superficiality.

It also gives us a reference to twin flames > twin souls > soul dualism.

Time to Reflect: Reality vs Delusion

The concept of mirrors and reflections are common throughout The Substance; a dualism between looking inward and projecting outward; hiding inside and fearing the outside. They both display inferiority and superiority complexes.

Once Sue comes into the picture, Elisabeth only sees Sue, and Sue only sees herself. Their egos distort reality and drive a wedge between them to the point that Elisabeth forgets that she is Sue.

“You Are The Matrix, The Matrix is You,” literally evokes The Matrix (1999) — we all have two states of consciousness; red pill vs. blue pill, wisdom vs. ignorance. There’s a manufactured consciousness and a constant battle between reality and delusion. This underpins the plot and Elisabeth’s character arc as she, Hollywood and society refuse to accept the reality of such an inevitable thing as age.

To quote Shakespeare’s Hamlet:

For anything so overdone is from the purpose of playing, whose end, both at the first and now, was and is to hold, as ’twere, the mirror up to nature, to show virtue her own feature, scorn her own image, and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure.

Translation: Hamlet proposes that what is seen onstage reflects what is real in our lives and in our world. Also, prepare for a tragedy.

In the last 20 minutes, Fargeat shifts gears with blunt-force precision, leaning into the absurdity of the Hollywood machine and the delusions of our new hero(?), Monstro Elisasue. It’s as though the film itself has become self-aware, reanimated as a cartoonish monstrosity. It’s gratuitous. It assaults us with so much visceral madness that it breaks the immersion, forcing us back into consciousness long enough to become cynical. But my guess is that we’ve actually been duped into fulfilling Fargeat’s prophecy — we’re now disgusted and dismissive. We perpetuate the narrative in the name of entertainment. At the most, we’re accountable. At the least, complicit.

It’s like Fargeat wants us to turn on her, just like the studio audience turns on Monstro Elisasue. It gives shades of Frankenstein’s monster, but instead of pitchforks, they’re grabbing mic stands. Elisasue is attacked while members of the audience continue to watch, some of which seem to be unsure if it’s supposed to be part of the show. Her mutilated body erupts with blood, hosing down the audience, cast and crew — all of whom just can’t seem to find the exit. It’s a sort of reverse-Carrie moment that feels like an eternity. Perhaps this is Fargeats way of hosing us all down.

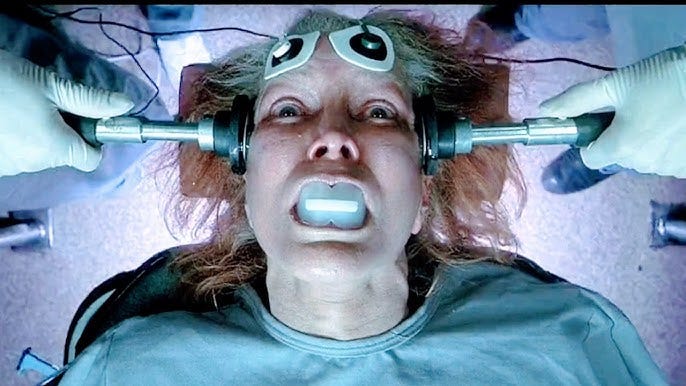

The director draws many parallels to other films. The ones I picked up on were the Kubrick films, Robert Zemecki’s Death Becomes Her, and Aronofsky’s Black Swan. Aronofsky’s Requiem for a Dream deserves a mention here too, another film about different states of consciousness, exploitation, substance abuse, desperation and irreversible transformation. Elisabeth’s arc is akin to Sara Goldfarb’s poor self-image and descent into madness. Her relationship with Sue gives shades of Harry and Marion’s in how they enable, betray, exploit and become permanently scarred, physically and psychologically. There were also a couple of moments that I thought were nods to Gaspar Noe films like the bloodied hallway looking a lot like the Irreversible tunnel and the bathroom in Enter The Void. The first is a story centred around a woman who falls victim to an extreme act of violence. Her, her lover and friend will forever be changed. It’s told through a distorted, mirrored timeline that shows the brutal act and the brutal reaction. Enter The Void also builds worlds around altered states of consciousness, life and the afterlife, and drug use.

At peace, in pieces.

The dying minute of the substance saves one final moment of delusion for Elisabeth, who crawls back to where it all began: her star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Now, her final resting place. It’s over the top, but The Substance delivers a masterclass in dualism and Theatre of the Grotesque. This is a fable, with a lesson in self-love. It is both cathartic and terrifying to witness the extent that Elisabeth will go to reject her true self, which is something many of us can see in ourselves. It hits close to home, gets under the skin, and burrows deep inside. There’s a lot of ~substance~ that may be overlooked for the glossy, sexy and crowd-pleasing aspects. That might be what Fargeat had in mind.

Seriously though, don’t beat yourself up.

Appendix

Notes that I decided to cull from the main article — mostly just screenshots though.

Birth and emergence

From the eggs and shots of Elisabeth laying in a fetal position, to what appears to be a birthmark, branding users of The Substance and marking the true, natural self.

Reflections vs refractions

Elisabeth fearing and fulfilling her destiny in three shots.

Distorted self-images: Sue sees her reflection in screens and technology

Elisabeth’s sees her reflection in relics of her past

And the things that shut her off from the outside world.

Escapism: Captivity vs Freedom.

Like a chicken, pecking its way out of its shell.

A prisoner.

Parallels

Irreversible (2002)

The infamous Irreversible tunnel and film with a distorted timeline that acts like a mirror, reflecting action and reaction; parallels with predatory nature of Hollywood; Elisabeth’s actions could be described as a violation of the self.

The hallway in Severance–a show about the two lives we live between work and personal life.

Requiem for a Dream (2000)

A film about substance abuse, the delusion that comes with addiction, the perils of ambition, a disrespect for elders, the predatory nature of society, pride, vanity and negative self-image.

Plagues & miracles of the bible

Flies

Boils

Leprosy

The Cripple

Death of first born